over de grens - verwijdering van vluchtelingen en migranten uit Nederland

autonoom centrum, maart 2004

# Expulsions through the years

> 'Working on Return' > Territory and refusal > Return of asylum-seekers who have resided in the Netherlands for a long time. > The future

Barring foreigners is not a new phenomenon in the Netherlands. In past centuries skilled and rich immigrants were given direct admittance to the cities while the down-and-out were kept out. Only in the 20th century did governments become interested in controlling immigration. Today the policy of returning illegal or undocumented foreigners is considered the essence of the immigration policy. The practice of the return policy, however, brings about illegalisation and exclusion from the social services of the society. Only recently the government has started to make a serious effort regarding expulsion. Previously there had been a long history of various measures and decrees, with little success.

# 'Working on Return'

The outline agreement of coalition-government Balkenende II speaks of a dynamic approach to the policy of return. In its November 2003 report "Working on Return," the cabinet, through minister Verdonk, states its conviction that the return policy must be more than the final piece of the legal procedure. In past years a lot of attention has been given to measures to limit the influx. They have led to an effective reduction of asylum-seekers. "It has also led to less attention than was necessary to the return of immigrants whose procedures have finished and other foreigners without a residency permit," according to the minister.

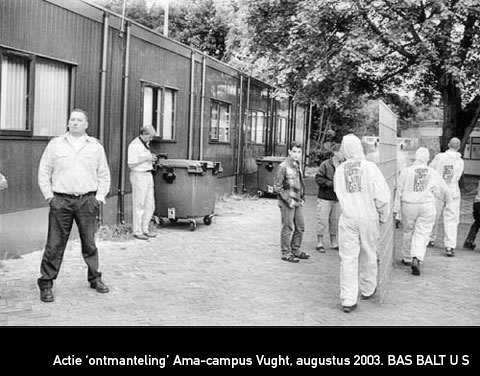

The report concludes that all asylum-seekers who have had a negative decision from the Immigration and Naturalisation Service (IND), but are still entitled to housing, living allowance and health insurance (for instance because they still have an appeal going) will in future be housed in return centres. These centres will have to be built. The current reception centres for asylum-seekers (AZC) will give way to 'return locations' and 'orientation locations' where asylum-seekers will stay pending a decision. With the 'return locations' Verdonk hopes to give a stronger signal that 'expulsables' will have to leave the Netherlands.

# Territory and refusal

From the perspective of effective border control, asylum-seekers who arrive at Schiphol Airport will in future more often be refused entry to the Netherlands. At the moment these asylum-seekers are mostly processed by the short 48 hours procedure at research centre (AC) Schiphol. Those who get a negative decision are locked up in the border prison "Grenshospitium" (Border Hospice), until an effective or administrative (i.e. put out on the street) removal. Prisoners in the Grenshospitium are officially not on Dutch territory. For those asylum-seekers at AC Schiphol, where further research into their story and identity is necessary, access is currently granted to the Netherlands by placing them in a reception centre. The cabinet plans to place this group (except those deemed by the IND to have a high chance of obtaining a residency permit) "in all cases if capacity allows" in the Grenshospitium.

Besides functioning as a deterrent for asylum-seekers this measure provides another 'advantage.' The agreement on International Aviation (Treaty of Chicago) places the responsibility with those countries from which a foreigner has travelled to take this person back, when refused entry. This obligation is valid irrespective of nationality and the availability of travel documents! This provides the Immigration Service IND with six weeks, instead of 48 hours, to deny an asylum request and expel someone without travel documents. Asylum-seekers often do not have travel documents when they report at customs. Finding out someone's nationality and acquiring travel documents is one of the major difficulties with expulsions.

Another advantage is that the Aliens Act states that the airline with which the foreigner has arrived is obliged to return the refused person to the latest point of travel outside the Netherlands. Free transport is therefore guaranteed. In addition the cabinet is going to try to recover the costs of expulsion from the foreigner. As the report states: it is being investigated if it is possible to demand a deposit at 're-entry' when someone hasn't 'paid back' the costs of his prior expulsion. Whether this will also apply to asylum-requests is as yet unknown.

Intensifying the control of foreigners/aliens is now being promoted as the most important contribution to the return policy. The Aliens Police will have more (wo)manpower, and the capacity to put aliens into detention will also be increased.

Reverend Hans Visser of Rotterdam's Paul's church says about the return locations: "These centres of Verdonk, we will never cooperate with them. No doubt about it. They'll be some sort of small concentration camps. The expulsion policy itself is a failure. The possibilities of supporting people whose procedures have ended and illegal immigrants have been severely restricted by new laws. We have to avoid that people end up in these centres. If people want to return, then voluntarily through other channels, not through these horrible centres."

# Return of asylum-seekers who have resided in the Netherlands for a long time.

At the end of January 2004 Verdonk published her once-only pardon measure. Of the 5800 cases of asylum-seekers that are in procedure for over 5 years, that were researched, 2097 will get a residency permit. Of the 9800 requests for legalisation because of harrowing conditions 220 people (2%) will get a permit.

The remaining group of asylum-seekers, that will be expelled with the help of the municipalities, consists of about 26,000 people. It will be attempted to acquire the necessary travel and residence documents for them in order to be expelled. If this fails the municipality will start a civil eviction procedure. The police, under authority of the Mayor, will carry out the eviction. For people that requested asylum before the new Aliens Act (before April 2001) there is a maximum period of 8 weeks for this procedure. For people whose cases are under the Aliens Act of 2000 there is a period of 28 days.

When expulsion is possible in the short term, the asylum-seekers will be detained in Expulsion Centres Zestienhoven (Rotterdam) or Schiphol. In other cases they will have to report periodically, will be contained in their freedom of movement or detained in a still to be founded return centre for up to 8 weeks. In this centre there will be intensive 'counselling.' There are 3 possibilities:

If return is impossible through no fault of the asylum-seeker, a residency permit can be given on the grounds of the "no fault"-criterion.

In other cases detention can (again) be imposed in an expulsion centre or another penitentiary institution. Precondition is that there is a sufficient prospect of expulsion.

If forced expulsion cannot be realised, the restrictions on movement or freedom will be ended as will residency in a return centre or detention centre. With the 4 biggest cities and the Association of Dutch Municipalities it is agreed that in these cases no housing will be provided by the municipalities.

The new policy will be implemented in the first half of 2004. Mid 2004 the first expulsion centre is meant to be operational. The expulsion centres will have 1500 places for asylum-seekers whose procedures have ended. The aim is to complete the project [deporting 26,000 people] within a period of three years.

Since the Balkende government established this policy, civil society has gone into turmoil. The Dutch Refugee Council (Vluchtelingenwerk) and clerical organisations such as INLIA are being flooded with responses from concerned citizens, action committees, schools, community groups and asylum-seekers themselves. They want to know what will happen to all those whose cases aren't considered harrowing. "I have not encountered such a civil unrest before" says INLIA-director J. van Tilborg. According to van Tilborg, all of the 2097 pardoned asylum-seekers, who are still in procedure, will have received a residency permit from the IND or the court anyway. F.Oosterhof represents action committee 'Van Harte Pardon' who support asylum-seekers whose procedure has ended. She wouldn't be surprised if concerned citizens form a 'human shield' when the refugees are about to be expelled from their homes or a centre by the Aliens Police. She already knows refugees who live behind closed curtains.

As a consequence of the new return policy of minister Verdonk thousands will end up in illegality, alderman A. de Vries of Middelburg predicts. "Because of the plans of the minister 26,000 people will have to be expelled? How are we going to do that? When people end up in the expulsion centres, in 65% of the cases it will be impossible to expel them because they have no documents. Of the people who can leave, only a fraction will do so. The rest will go into illegality. How effective is such a policy?" Almost half of the population (47.5%) thinks that more people should be up for pardon. A group of 81% agrees with organisations and individuals who want to provide housing to people in harrowing conditions who would otherwise be expelled. 29.5% are personally prepared to take such a person or family into their home in order to prevent expulsion.

The big cities will possibly still provide housing for asylum-seekers whose procedures have ended. They demand from the minister that the state will house asylum-seekers who want to return, but who are unable to do so. The municipalities foresee a great number of problems because there is no housing planned for people who cannot leave the Netherlands, for example because they cannot obtain a travel document.

Van Kalmhout, professor in aliens and criminal law, says Verdonk hasn't learnt from the past. According to him the effective yield of expulsion has been decreasing over the last few years. Of the asylum-seekers and illegal immigrants in detention five years ago, 50% were effectively deported. By 2003 this figure had dropped to 35%, according to his provisional data. The average duration of detention prior to expulsion has also increased from 50 to 60 days at the end of the nineties, to 80 days in 2003. Verdonk's policy is part of a progressing line of repression in which all blame is placed on the asylum-seeker. Van Kalmhout thinks Verdonk's requirement that asylum-seekers have to prove their innocence in not being able to acquire travel documents is unreasonable. Embassies do not provide proof. In criminal law there is no such requirement in which the burden op proof is reversed, and he sees no reason for there to be one in the Aliens Act.

The Netherlands does not live up to the Treaty of the Rights of Children. Children's rights are mainly violated in the asylum policy. Dumping young asylum-seekers on the street, as happens now, is a violation according to the UN-committee for children's rights. The committee also questions the legality of detaining children asylum-seekers. "All children in the Netherlands awaiting their expulsion should be provided with adequate education and housing" the committee states in its report of February 2004. In the current policy asylum-seekers whose procedure has ended are entitled to housing for another 28 days. After that they're on the street. "It seems to me that the minister will now have to adjust her policy with lightning speed," T. van Os, chairman of the advice committee on alien affairs states.

# The future

In the second half of 2004 the Netherlands will chair the European Union. The date May 1st 2004 will be a turning-point in the European asylum and immigration policy. The 5 year deadline in which a large number of subjects have to find resonance in EU-regulations will expire. In the immigration policy it concerns measures on illegal immigration and illegal residence, including the expulsion of illegally residing persons.

At the same time discussions are being held on border control. It is possible to distinguish two trends: on one hand a shift from physical border control towards guarding 'internal' borders of the welfare state and the labour market. On the other hand the 'de-nationalisation' of border control, which means that the role of parties other than government (for example the moves toward airline companies) will become increasingly important. Parties involved may include: municipalities and private companies such as airlines, bus and transport companies. There will also be a shift of physical border control to a supranational level, e.g. the outside borders of the European Schengen countries.

Because of the continuing pressure of immigration the proposed restrictive policies have been to little avail. The policy stipulates too many options, most of which have been ineffective. However the policy has served as a deterrent and has had a preventive effect on the influx.

The long-term prospects of the upcoming return policy are ever more drastic measures: 'closed environments,' deportation centres, raids, controls, erosion of the legal system. This while the Netherlands has already grown into one of the most restrictive countries in Europe. The Scientific Council for Government Policy, in its report 'the Netherlands as immigration country' formulated the situation as follows: "the high hurdles that western states put up will also lead to the further commercialisation and criminalisation of (illegal) immigration." This policy is certain to stimulate the creativity of immigrants in search of a better future. Selective indignation about immigrants who hide themselves or their identity is therefore inappropriate. Immigrants deserve our support.